Last Updated on 13/02/2024 by Admin

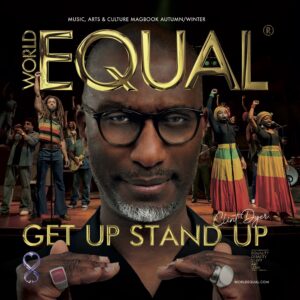

Above image credit: The Company of Get Up, Stand Up! The Bob Marley Musical – photo by Craig Sugden on the West End Musical sensation on the life of Bob Marley, Directed by Clint Dyer.

Clint Dyer already has, and again is, taking the West End by storm! Not just because of his talent and understanding of his craft, but also in the historical sense that he is the first black director to conquer the West End …..twice! This is no one-time-fly-by-fluke!

Clint is an actor, writer, director and the Deputy Artistic Director of the National Theatre in London. Additionally, Clint is also the director of the Bob Marley musical Get Up, Stand Up! Currently running in the West End to great audiences and positive critical response. He also directed the Olivier award-nominated The Big Life, a musical that started at the Theatre Royal Stratford East in 2004 and was so successful it transferred to the West End in 2005.

Clint only ever wanted to be a footballer, and by the age of fifteen, he was well on his way. He tells us, “If I bump into people who went to my school, they ask, ‘How come you’re an actor? We thought you were going to become a footballer.” There is a good reason why he abandoned the game. The son of Jamaican-born parents, Dyer grew up in East London in The 1980s and felt loyalty to the local team, West Ham – until he- went to see them play. “My dad took me there, and, bless him, he didn’t realise how much it would scar me – thirty-thousand people throwing bananas at the only black man on the pitch! I was abused to the point I stopped going – and playing – for ten years”.

Luckily, Clint discovered theatre. It is our privilege, in this special edition of World Equal Magbook, to have the opportunity to talk with the man himself and hear about his past, present and future as a black director in Britain, making extensive new waves. Here Clint has a conversation with World Equal partner and award-winning novelist, film and theatrical producer Teddy Hayes.

Teddy Hayes: Clint, you were an actor long before you became a director. And during your acting career, you had several things, like Love Me Still, Act of Vengeance, The Club and SUS. Tell me about your most memorable experience as an actor.

Clint Dyer: I suppose what I’d say is the benchmark stuff that really got me to the next stage was working with Mike Leigh at the Theatre Royal Stratford East when I was about 25. That got me into a whole other category. Mike Leigh was huge, and I did that with Marianne Jean-Baptiste, Gary McDonald, Kathy Burke, and some other excellent actors. And that was a definite benchmark. And then everything opened up in various ways, and the TV roles I got were a lot bigger and more significant. Then Linda LaPlante wrote SUS, a two-hander for me to do. And that was a beautiful part. So, as a result, I did some quite substantial TV stuff. And then I acted in SUS at Stratford East, then we did it at the Young Vic, and then we toured, and after that, they ended up making a film of it. And the film ended up going to America and throughout the world, and it’s actually still being played, and it’s on BBC iPlayer now. So, if somebody were following my career, I’d definitely say that part has become synonymous with me because of the number of times I did it and because I made a movie about it. So, I’d say that was a big momentous part of my acting. But aside from that, doing Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom at the National Theatre was incredible. Just the quality of everything around me, the text, the director, the cast, the design, the size of the stage at the National. It all lent to making it an undoubtedly overwhelming experience. I didn’t want it to end.

Teddy Hayes: When I saw you were made Deputy Artistic Director of the National Theatre in London, I felt very close to the way I felt when Obama was made president; such a momentous event.

Clint Dyer: Listen, I understand; being here as a black person, I never thought I’d see it in my lifetime, much less me being it.

Teddy Hayes: You moved from acting to directing. What was the transition like?

Clint Dyer: I suppose the funny thing for me was I was always writing but not really telling anybody. And so after The Big Life, what happened was I got involved in three director’s courses that Stratford East held. In three years, they did three courses. I was on board as an actor for two of them, and for the last one, I finally picked up some courage and said I’d like to do the course myself. And I think Phillip [Phillip Hedley, former Artistic Director of Theatre Royal Stratford East] was waiting for me to say it. He didn’t want to push me, but he was leaving all these doors open for me. And he’d left it up to me when I wanted to take that next step. Interestingly, my writing came from working with the Royal Court theatre as opposed to Stratford East, and you’d have expected it to come out of Stratford East. But then we set up the musical theatre course. So, it was a natural progression for me to think, Oh, I’ll do a musical. Now anybody who knows anything about directing or about theatre knows that for a musical to be the first thing you direct is madness. That’s just like overloading yourself with crazy. You’re meant to start with a two-hander in a little theatre, but I started off with a musical that ended up going to the West End.

Teddy Hayes: That was incredible

Clint Dyer: What I did feel at the time was that there was a massive, not rejection, but a snobbery to the fact that I, the actor, had gone and directed something that had gone straight to the West End. And people didn’t want to kind of admit that was possible, especially for a black actor to come along and do that. So then I kind of felt like I had to get into straight plays and all that sort of stuff. You know, I literally had to start again, and I think it’s actually through my writing that I convinced the Royal Court theatre to give me a play to direct. It was only after I’d written and directed at the Royal Court that Kerry Michael [Stratford East’s new artistic director] actually asked me to do a play there. But no other theatres came in. I got it shown in the West End, but not one theatre rang me up and said that they wanted to have a chat. I’m not talking about giving me a job, we’re just talking about having a conversation. Maybe because I was still acting, people were like, well, he’s acting, he’s in that show, how can he be directing and acting? So the transition from acting to directing wasn’t smooth. To put it in nicer terms, it was very integrated. And I couldn’t not work, I had to do both because I had to pay the bills, so I couldn’t have thought, Right, I’m just going to be a director.

Teddy Hayes: Speaking of musicals, when I’ve spoken to people, they always say the same thing, that the National doesn’t do musicals. In your role as Deputy Artistic Director, do you see a possible future for musicals at the National?

Clint Dyer: Absolutely. I mean, we’ve got a musical theatre department. We’re constantly talking about developing musicals. Rufus [Norris, current Artistic Director of the National Theatre] recently directed a new Christmas musical, a family musical, so we’re most definitely developing new musicals.

Teddy Hayes: I read something you said concerning the production of Death Of England. You said, “White people often don’t think black people can write for white people” When I read it, I said to myself, ah-hah, this is a man who understands the dilemma of black writers. Could you elaborate on that statement?

Clint Dyer: Well, good writing is good writing. And you can only do that if you have experience, a good imagination, or a good ear. The point is that a lot of white practitioners don’t hang around or investigate or do research into other cultures to be able to feel comfortable enough to write about them. Black people here are overwhelmed with white culture, so it’s absolutely nothing for us to write for white people.

Teddy Hayes: I agree. What matters most is that the writer must be skilled in the craft of storytelling, have an understanding and sensitivity to the culture they are writing about, and build the story in a way that will keep the audience interested. For example, many people don’t know, in the original detective story about the black detective Shaft, which became a hit film, was written by a white guy named Ernest Tidyman.

Clint Dver: I didn’t know that.

Michael Duke as Bob Marley – photo by Craig Sugden.

Teddy Hayes: Yeah, what happened was Hollywood found that black movies were making money. So they said, ” Let’s get this white guy with a detective story to turn his detective into a black guy, and that’s what happened. And nobody questioned that. So, it warms my heart to hear you say that because I think that in your position, it’s important that you state those things that are obvious to us as black artists that may not be so obvious to people who are not black. So in your role as Deputy Artistic Director, what influence do you think you might be able to bring to the National Theatre?

Clint Dyer: The obvious stuff is, inherently, I bring more diversity. Coming from Stratford East and seeing how the artistic director there managed to make it speak to the community, I felt like there are some ways of encouraging that feeling and that notion that aren’t as obvious as you may think. There’s a lot of unconscious bias that I can bring to light. So just from that perspective, I feel like what I’m doing is helping them do what they want to do. And it’s really weird because it’s not that they don’t want to do it. There’s a lot of stuff they just don’t know how to do or don’t know how to put at the forefront. So it’s very easy to lead them to the destination because actually, they want to go there. So l don’t feel any sort of opposition to it. 90% of the things that I suggest are taken on. Sometimes there are practical difficulties in terms of diversity and the spread of diversity within the onstage and backstage environment. Sometimes, there are contextual things that make my desires impossible. For example, we’ve been searching for someone to fill a particular role and anybody from the global majority who can do that job is going to get paid more money somewhere else. So the problem becomes two-fold. It becomes finding people from the global majority who can do the job and then finding people from the global majority who are interested enough to work in a theatre. And also, there’s a timescale thing that we, unfortunately, have to accept. Let’s say we decide to create a job to address one of the things we are trying to do. The first thing is it takes three months to actually get the advert out, do the interviews, the process of that and then you pick somebody. Then they need three months to six months to leave the position that they’re in because they’re working most of the time. So you’re talking six months from saying we need this position. And that’s the minimum.

Teddy Hayes: And, here is something that I bet many people will be surprised at. You’re the only black guy I know who’s directed two shows in the West End.

Clint Dyer: I know, and it’s really interesting, isn’t it? Because there are a lot of argy-bargies about who did it first. Some people say, “Oh wait, I did it first”, then you really check it out and find out, oh, no, that was an Arts Council initiative the way you got that one, or that wasn’t actually on the strip on Shaftsbury Avenue, or, your one was at a music venue. And it’s so much back and forth connected with that, so I just say ok, you lot did it first (laughing good-naturedly). So I can’t be bothered by that. But I know that nobody else has done it twice!

Teddy Hayes: This takes my thinking back to when I worked in commercial theatre in New York and how the public theatre there created shows under their non-profit theatre status and then developed them for commercial consumption. This was done with Bring in Da Noise, Bring in Da Funk, Caroline or Change, A Chorus Line, and Hamilton. Do you plan to do this for shows produced at the National Theatre?

Clint Dyer: In the National Theatre, the NTP is the National’s touring company. So that’s kind of built within the whole model of the National Theatre that certain shows get picked up and taken to the West End, or they can go on tour in England, or to Europe, or some will go to Broadway. So that’s completely and utterly always in the thinking. In those cases, the National will be the producers, but theatre owners have to decide if they’re going to back it. So it’s never just a case of, is it something we want to travel? We had Death of England going into the West End, and Covid killed it at one point. So, it’s tricky. It is always a balance of timing and desire.

Teddy Hayes: You’ve now done Get Up Stand Up, which is a project that people have been threatening to bring to the West End and Broadway for the past thirty years, and for one reason or another, it never happened. The first thing I did after I saw the show, which I liked tremendously, was, I opened the programme. And it wasn’t a surprise to me that they had to get a lot of different producers to make the show happen. And the main person putting it together was Chris Blackwell, the owner of Island Records because he owned the rights to Bob Marley’s most famous recordings.

Clint Dyer: Yeah. You know it was funny. When I did The Big Life, I met Rita Marley, and she told me she wanted to do a show about Bob Marley. I was like, please, please, please.

Then I hadn’t started writing. So, I was really just thinking of directing. Then she went to Kwame [Kwei-Armah, Artistic Director of the Young Vic] and Kwame became the go-to guy because there were only two of us in terms of profile that could have done it. Of course, many people could have done it, but as we know, it’s a profile thing that makes a lot of these deals come together. And it still took over a decade for it to come all the way back to me.

Teddy Haves: I think you did an absolutely great job telling the story because it’s a complex story to tell. And the thing I immediately picked up, having also seen The Big Life, was, how you used the DJ in the box slightly off-stage. And then I remembered the ladies in the balcony box from The Big Life. So it was very effective in both cases.

Clint Dyer: Well, funnily enough, the Marley show originally had more things happening in the DJ box, including an interview with Bob. But I had to end up cutting them out because the first half was too long. But the beautiful thing about doing that thing with the box is that it immediately breaks down the space between the audience and the stage.

Teddy Hayes: I think the balance was very tricky in the story. Many people focus on Bob Marley’s relationships with many women, and because of that, some people say, Oh, he was not very responsible. But on the other hand, the music was so overpowering that most people I spoke to said, Okay, well, here was a guy who wasn’t necessarily the most simple guy. He was a complex person, and your direction showed that in as much as he had to deal with political realities, family responsibility, and his own spiritual path to travel. And I think it made it a much more interesting and substantial play. And I think it’s going to do well all over the world. How many touring companies have you already got going around the world?

Clint Dyer: They’re being very cautious. It will depend on how we run in the West End, on whether and where we go next. I do believe it will travel. But I think they’ll see how long we can run here in London, and then they’ll go, okay, we’ve made our money back and take it from there. The development process, as you know, has been so long, and they’ve spent a lot of money. I mean a lot of money. I think they’ll go, right? Finally, we’ve started recouping and can now go to other cities.

Teddy Hayes: Yes, I can understand that from a business point of view. But looking at another business model, take what Andrew Lloyd Webber and Cameron Mackintosh are doing. They clone their shows quickly and send them out so they don’t have to make all the money back on the first show. Instead, they might make it back on three plays running simultaneously. By doing that, they’ve created a very large market.

Clint Dyer: I know, I hear you, but I’m not the producer!

Teddy Hayes: I know, and I’m the devil’s advocate here.

Clint Dyer: The interesting thing is I’m confident that black American audiences will actually spend the money in a way that black British audiences haven’t. But what’s beautiful about what’s happening right now with the show is that all types of people come to see the show. And they were basically expecting mostly black people to come. I think they can’t look at our audiences and estimate how much black Americans will dig it. They don’t know that yet. So I have a feeling that in America, audiences will be predominantly black in a way that the audiences aren’t predominantly black here.

Teddy Hayes: True, there are thirty million black people in America. But at the same time, in America, you’ll get loads of white people who love Bob Marley. I saw Bob Marley for the first time in 1978 in New York’s Madison Square Garden. That was the first time I’d ever seen people hold up their lighters. Then it suddenly hit me. This guy’s not a rhythm and blues or soul star. This guy’s a rock star. And the predominant part of the audience was white.

Clint Dyer: I’ll tell you what it is, though. The message of Bob is so black that I think people will tune into it in America.

Teddy Hayes: They will, without a doubt, but don’t think white people won’t too. They will. They will come in droves because of the music.

Clint Dyer: Look, we’ll see, fingers crossed. Clearly, I’ve never been dictated by money from my moves in this industry, so that would be nice. But that’s not why I do what I do.

Teddy Hayes: But, also we know as artists and theatre-makers that theatre is one of the very few places within the entertainment industry where one can create something and make enough money to pass it on to the next generation. Because you are the director, as long as this show runs anywhere in the world, you’ll get a piece of it.

Clint Dyer: Yeah, I hear you.

Teddy Haves: I have to say that because when I talk to many people in the arts, they often don’t consider that and having worked many years with the late iconic filmmaker and Broadway producer Melvin van Peebles, one of the first things he taught me was whenever possible get a piece of the long-range profits. Because that’s what you can pass on to your next generation, even after you’re long gone.

Clint Dyer: Yeah, I know, exactly. And writing plays as well. So that will always be something. They’ll always come back and keep paying as well.

Teddy Hayes: Wow, the time has really flown by. Thank you so much for talking to me.

Clint Dyer: Listen, it’s been great. So you’re doing a publication? Is that what this is for?

Teddy Hayes: It’s called World Equal, and it’s an arts-based Magbook. It comes out of Northern Ireland twice a year.

Clint Dyer: Northern Ireland? Amazing. I wasn’t expecting that. That’s great.

Teddy Hayes: I am one of the co-owners of the Magbook, and the publisher came to me and asked me what I wanted to do for this special edition of the Magbook. I said I wanted to do something on Get Up Stand Up because it’s about a black musical icon directed by a talented black guy, making this an important project. She said OK, so there you go.

Clint Dyer: Thank you very much

Teddy Hayes: My pleasure.

Sophia Mackay as Judy Mowatt, Gabrielle Brooks as Rita Marley, Melissa Brown Taylor as Marcia Griffiths – photo by Craig Sugden.

World Equal… The scope for future productions is broadening as we see positive change happening in real-time. The first black person to be a deputy director of the National Theatre London is a huge deal. Seeing Clint succeed twice as a director on the West End bolsters it further, and it’s wonderful to experience. If you have seen the beauty of the diversity within the great barrier reef without pollution, it’s a good model if you want to visualise how a new future can thrive and sustain itself within a diverse society of arts and culture. World Equal will be there to see it happen.